Last week in our dialog about resistance, the idea of color blindness came up in discussion. It was presented as a form of resistance to racism. We’ve all heard the phrase “I don’t see color.” That and phrases like “we’re all one race, the human race” seem like loving and inclusive statements on the surface. Upon closer examination, they ring as hollow as Michael Scott’s famous words in season two of “The Office” when he said he didn’t see “collars”. He said he was “collar blind” while on a field trip to the warehouse to see what life was like for the blue collar workers in the basement.

What I find interesting about color blindness is that in my experience, the people who claim to have this honorable ailment have always been white. It seems to be a condition that ails only the privileged. People whose skin tone has a darker hue tend to be immune to the disease of color blindness.

For POC, the color of their skin, facial features, and hair texture are all reminders of their heritage. It isn’t something to be blind to, but rather something to be proud of. Our color is something we celebrate as a God given gift. It is part of how we identify the beauty of who God made us. There is great dignity in recognizing who we are and how we are created. Recognizing, making space for, and celebrating the beauty of culture is how genuine love and inclusion are expressed in society. However, POC are also aware of the cultural taboo that can accompany our pigmentation.

I rarely walk into any space outside of my home without feeling the weight of being a black man. A few weeks back I drove to a neighborhood I didn’t live in to pick up some shoes my wife was purchasing from a stranger through social media. She told me she ordered shoes for her sister. My instructions were to drive to the address, go to the front porch, pick up the shoes, and leave $20 under the mat. This sounded simple enough.

It was after 9pm and obviously dark (here in the suburbs of SF) when I drove into this neighborhood and parked my car on the street. I was having trouble finding the house so I started walking around the dark cult-a-sac looking for the address my wife had given me. I walked to one end of the street and didn’t see the house number I was looking for. As I turned to go back to my car, I began to fear that someone would see a 6’3 black figure walking around in the neighborhood at night, and call the police.

After growing increasingly anxious about being in this neighborhood alone at night, I quickly jumped back into my car and drove down to the end of the cult-a-sac. I found the house I was looking for and walked up to the dark porch looking for shoes. I didn’t see any shoes, so I rang the doorbell. No one answered, and I stood their on the porch feeling more and more angst as I didn’t see any shoes. I was reluctant to investigate too much for fear of looking like I was breaking into the house, so I went back to the car and called my wife.

The reason I had to go back to my car to call my wife was because I purposely left my cell phone in the car in case someone did call the police. I didn’t want to have anything in my hands or pockets that could have been mistaken for a gun when they arrived. This happened not long after Stephon Clark was shot by the police in Sacramento (which is just an hour and a half East of where I was standing). The incident was fresh in my mind. I didn’t have the ability to conjure color blindness to still my anxiety as I began to see myself in a similar scenario as Clark.

I called my wife. She told me I was looking for baby shoes for her sisters newborn, and I walked back to the porch and found them. I put the $20 under the mat on the porch and left. The police never showed. Possibly no one called or I got out before they arrived. Who knows. The point is, I did not have the luxury of behaving as if the world is blind to my color and that stereotypes don’t have life-and-death consequences for people like me.

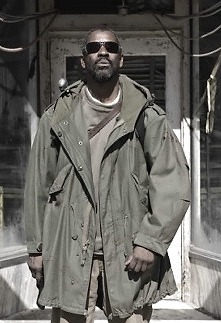

I’ve heard more than a few white people share stories of their own feelings of fear simply driving through certain neighborhoods. I wonder if any of my color blind brothers and sisters are suddenly “healed” of their condition when faced with these scenarios. I’d imagine their blindness is a lot like Denzel’s in “The Book of Eli”, it comes and goes as needed.

(If I spoiled the movie for you, you have no one to blame but yourself. That movie’s been out for like 100 years).

When faced with real world scenarios, shallow ideology like color blindness prove to be less than helpful. It is not a stance that helps rid the world of systemic racism or implicit bias. Ethnic and cultural sameness is a tyrannical way of seeing the world. Democracy and freedom is about being able to exist in the same space with diverse cultures being fully recognized, not disregarded. Being proud of your culture and celebrating differences are not evil. Racism is, and continuously denying the beauty of diversity is a form of racism.

Blindness has two definitions.

- the state or condition of being unable to see because of injury, disease, or a congenital condition.

- lack of perception, awareness, or judgment; ignorance.

Which of the two definitions most applies to the people you know (including yourself if appropriate) who are “color blind”?